When people wave to you through the windows of your home, you probably wave back. If so, you're using a handy property of glass that we all take for granted: it lets light pass through it pretty much unimpeded. If you have a cat, it probably curls up on your window ledges in the sunlight. If so, it's taking advantage of a different property of glass: it lets heat pass through it too. Now glass is brilliant stuff and most of the time we're happy to let light and heat stream through it in both directions without a second thought. But in extremes of summer and winter, that's not such a good idea. On hot summer days, wouldn't it be cool (pun intended) if your windows reflected back the sun's heat automatically? Likewise, in the dark depths of winter, wouldn't it be great if the windows of your home helped to stop all that expensive heat from escaping? If you have heat-reflecting glass in your windows, that's exactly what will happen. Let's take a closer look at how it works!

How is heat-reflecting glass made?

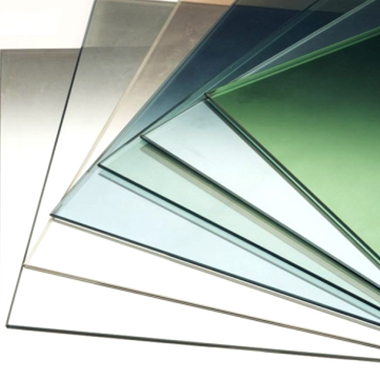

Heat-reflecting windows are usually sealed, double-glazed units—ones with two panes of glass separated by a noble (unreactive) gas such as argon that improves insulation (stops heat from escaping in air drafts). The inner surface of one of the panes of glass is given a very thin reflective coating, usually made from two or more layers of metal or metallic oxide (typical metals include titanium, zinc, copper, tin, and silver, and typical alloys include brass and stainless steel). The coating has to be microscopically thin if you still want to see through your windows, but you'll notice that it does give them a slightly brown or gray color. The exact form and thickness of the coating can vary quite widely from manufacturer to manufacturer. In early coatings, it was often a layer of silver sandwiched between two layers of metal oxide. But window makers such as Pilkington discovered they could get better results with a layer of silver, a layer of metal oxide (made from a metal other than silver), and a third metal oxide layer on top. This improved "recipe" seemed to reduce the emissivity while keeping the light transmission high.

Coating the glass

Typically, the heat-reflective coating applied in one of two ways. One way is a process called sputtering, where a thin film is fired onto the surface of the glass to make what's called soft-coated glass. The other process involves heating glass to high temperatures in a chemical vapor, so the coating material condenses onto its surface. That makes what's called pyrolitic or hard-coated glass. The coating in soft-coated glass is relatively delicate (gradually eroded by moisture and air and easier to rub off), so it's used only on the inside face of sealed double-glazed units. Hard-coated glass is slightly less effective at reflecting heat though much more robust, so it can be used in single-pane windows (though that also makes it less effective as heat insulation, since the air gap in double-glazed units plays a major part in retaining heat).

How does heat-reflecting glass actually work?

Cooler in the daytime

Imagine it's a blazing hot summer's day and the sunlight is shining into your home. Heat-reflecting glass lets visible light pass through it virtually unimpeded, but the metallic coating reflects longer-wavelength infrared light very effectively, much like a mirror. So sunlight enters your home as normal, but "sunheat" is reflected back out again. Even when the sun's moved around and isn't shining directly, objects warmed by infrared and ultraviolet radiation from the sun (like houses, cars, streets, and so on) can still re-radiate infrared radiation into your home. But heat-reflecting glass will simply reflect that back out into the world. With less heat entering your home, there's less need for air-conditioning, so heat-reflecting glass can help you cut your bills, even in summer.

Warmer at night

Now imagine it's a freezing winter's night. There's no light or heat from the sun coming into your home, but you've got a wood burner blazing away making your home nice and warm. If you have normal doors and glass windows, roughly a quarter of the energy you're producing inside your home will leak through them into the cold world beyond. Even with sealed, double-glazed windows, you lose quite a lot heat this way. How come? Heat from your home warms the inner pane of glass (by conduction, convection, and radiation). Now there's an air (gas) gap between the panes of double-glazed windows, so heat can't easily escape by conduction or convection. But the warm inner pane gives off infrared radiation, which radiates through the gas between the panes to the cold glass of the outer pane and the cold night beyond. If you have heat-reflecting glass, something different will happen. Like a camp fire, your wood burner will throw off infrared radiation. It'll travel out in straight lines to your windows and the metallic coating will reflect it most of it straight back into the room!

How much difference does low-E glass make?

Relatively little heat is lost (emitted) from windows like this—and that's why they're sometimes called low-emissivity, low emittance, or low-E glazing. You'll sometimes see heat-reflecting glass referred to as low-E2 (low-E squared), which is a marketing name for improved low-E glass. Since reflecting units allow less heat to pass through them, they have considerably reduced heat transmission (a lower U-factor) and increased heat insulation (a higher R-value) than ordinary double glazing.

Apart from using U-factors and R-values, you can also compare different low-E windows using a measurement called the solar heat gain coefficient (SHGC). If you're interested in windows that reflect the sun, you want this measurement to be as low as possible (unlike with passive solar buildings that soak up solar energy, where you want it to be as high as possible). Visible/visual transmittance (VT), which ranges from 0 (completely opaque) to 1 (completely transparent), gives you an idea how much sunlight still gets through a window that's been coated. SHGC and VT are sometimes combined in a single measurement called LSG (light to solar gain); higher values mean more light and less heat.

What are the drawbacks?

Every new technology brings its problems, and low-E glazing is no exception: what you gain in heat insulation you might lose elsewhere. Generally speaking, the better a window reflects heat, the worse it transmits light, so there's always a compromise between what's technically called visual transmittance (letting light through) and infrared reflectance (bouncing heat back).

Since they must reflect some light, low-E windows with metal coatings cannot be perfectly transparent, and their (typically) blueish-green color might not be to everyone's liking (or appropriate for every kind of building).

Low-E coatings tend to be quite fragile (since they're so thinly applied); they can get scratched during manufacture or installation or they can wear off naturally through weathering or through the gradual deterioration of other window components. Finally, low-E windows are obviously more expensive than ordinary glazing and it's important to ensure that the extra cost is justified by good energy savings. Thankfully, the payback time is quite short, typically 2–6 years.

The Related Glass Supplier In China:

Wallkingdon Glass is a leading glass supplier in China for architectural and interior glass and offers a variety of tempered and laminated glass products to satisfy a wide range of applications.

If you have any question for any type of glass , pls kindly contact us via enquiry@wallkingdonglass.com